(written from sea; pictures to follow once we arrive in Cairns)

The village of Ireupuow lies atop a promontory overlooking Port Resolution, one of the many natural harbors "discovered" by the incomparable Captain James Cook, who practically invented the South Pacific. At the time Cook's ship "Resolution" made its way into this large cove surrounded by jungle vegetation, steaming volcanic vents, and natural hot springs, the bay was much deeper than it is today. A series of earthquakes and tremors have since raised the sea bed so that today it lies just 3-4 meters below the surface. We arrived at first light on a Monday, after a 4.5 day passage from Fiji.

Immediately, we realized we were in a new kind of South Pacific. Earlier, I have written about the gradual leaving-behind of western-influenced cultures and norms, and the island of Tanna in the country of Vanuatu, completes the departure. Around us are puffs of steam emanating from jungle canopies, bamboo-and-bark ladders descending to the hot springs welling up along the steep shoreline, and the happy whoops of women and children coming from several distinct collections of thatched huts atop the vegetation-lined cliffs that line this bay. Some of the huts are built in trees, and that night, as we survey the land, it is apparent that there is no electricity whatsoever in these villages. It's dark like the ocean at midnight.

The next day, we go ashore and pay our respects to Stanley, the chief of Ireupuow. He is the second son of Chief Ronnie, the former chief, who died just over a year ago. Unusually for the South Pacific, in Vanuatu, the traditional patrimonial lineage passes over the first-born and it is the second son who inherits the title. When asked, Stanley later relates the Biblical story in Genesis where Isaac's second son, Jacob, at the urging of his mother Rebecca, deceives his father and gains the birthright and blessing that ought to have been the province of Esau, the oldest. In Vanuatu, at least in this village, the scripture is used to explain the cultural tradition of the second son chosen for lineal authority. There's a Presbyterian church (more a thatch-covered, wall-less canopy, with rough-hewn benches), a cinder block Seventh Day Adventist building, and, marked by a red cross, the village's dominant sect: the Jon Frum Movement.

In the 1930s, frustrated by the rigidity of the Presbyterian missionaries, Tanna natives began to talk about a (still) mysterious person named Jon Frum - said to be the brother of the god of Mt. Tukosmera, one of the island's several volcanos. By the time WW II came to the islands, the appearance of ships, jeeps, freezers, etc. seemed to bear out one of Jon Frum's central prophecies: the impending arrival of an abundance of wealth. Naturally, the Red Cross, with its clinics and hospitals accompanied the troops. Soon, Tanna followers of Jon Frum began to display red crosses, which today are visible in most of the villages. Chief Stanley did allow as to how many of his villagers attended all three churches, and smiled when I pointed out that it's important to cover all one's bases. When asked how long villagers would wait from the (re?)arrival of Jon Frum, one reference cites a reasonable response: "How long have Christians waited?"

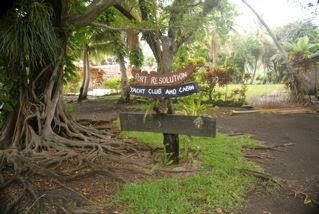

As we got to know Stanley, he let us know that there are actually two chiefs in each village - one ministers to the day-to-day issues and grievances; the other sets the longer-term direction and policies of the village. Stanley inherited the latter role; his father wore big shoes: he built a so-called "yacht club," creating a formal port of entry for Port Resolution (allowing boats to arrive at this upwind anchorage before proceeding downwind to the rest of the archipelago); he revitalized a decaying set of school buildings and has created a primary and secondary school for surrounding villages; and he had built (and then, after going off to school, personally staffed) a health clinic for the villages.

To appreciate the value of these three innovations, it's helpful to know that there are no paved roads on the island, and that I can count the number of cars within 25 miles on one hand. There is no indoor plumbing, and all food is cooked over wood fires in a hut designated for cooking. A village itself is traditionally laid out: about 20 families each occupy about an acre of land, with each plot surrounding a large common area consisting of a decidedly-unlevel soccer field. The huts are each about 15 feet wide by about 30 feet long, whose structures rely on hand-hewn branches from the banyan tree. The outside coverings vary: some use the unstripped reeds known as jungle cane, laid one against the other, vertically, slipped between horizontal runs of small branches. Bindings are twisted coconut fiber, tied in knots at the junctures. Others also use the cane, but stripped to its inner core, and then they use two layers - an inside wall and an outside wall, with dried palm leaves laid as a sort of insulation between the two vertical sets of cane. Still others use scraps of galvanized metal, haphazardly arranged and wedged, and still others use palm leaves, thatched. The most elaborate are the woven walls, where strips of palm leaves are interwoven into elaborate cross-hatch patterns. All of the roofs use the palm leaves, woven into thatches that lay, shingle-like, across the banyan branch roof structure. Windows are openings in the walls, with "planks" of palm trunks arranged into a covering of sorts.

The water for the village comes as a result of the vision and hard work of Chief Ronnie's father, who mobilized the village decades ago to dig a trench from a mountain spring 10 miles away, and to lay a water pipe. The village has a handful of gravity-fed pumps scattered about for washing and cleaning, and many villages lack even a supply of water, requiring women to walk to nearby springs lugging jugs and bowls.

Each family's "compound" has a slightly different look and feel, but in general, imagine a collection of thatched huts opening on a common courtyard of sorts, with the entire collection of family compounds surrounding the soccer field. The village straddles the bay, where we are anchored, and, just across the promontory, lies the southern ocean-abutting edge of Tanna, with its picture postcard white beaches, the gentle surf of the South Pacific on the shore side of a small offshore reef. Children run and play, men lounge, and the women work. Pigs and chickens grub for food among the grasses. Women work hard, from dawn to late evening, collecting firewood, food, cleaning, raising children, weaving, and tending to gardens.

The next day, we took a teeth-rattling, bone-jarring 4-hour, 25 mile trip in the village's pickup truck (along with about 15 villagers) to complete our immigration and custom formalities. On the way, we had to wait an hour for the rain-swollen, ash-bottomed river that runs alongside Mt. Yasur, (the very active volcano that attracts boaters and tourists alike) to subside sufficiently to allow the truck to cross. Eventually, after much hemming and hawing by the villagers, the driver put the truck into gear, headed down the ashen slope, turned the wheels upstream, and, with Jennifer and I mentally planning water escapes, crossed the 2 foot deep, 75 foot wide river safely.

Once in Lenakel, a dusty town of small cinder block shops and buildings, I sat and talked with the head of the local fisheries development program, charged with encouraging locals to expand their fishing activities. One thing led to another, and as we waited until 2 pm for the promised 1 pm opening of the immigration office, we got to talking about the roles of men and women in Vanuatu society. Like Stanley, in his description of the Genesis treatment of Isaac, Esau, and Jacob , the Bible immediately came into play: he too cited a verse from Genesis: "Woman's desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee." To this member of the Vanuatu middle class, women exist solely to serve man, and women had no say whatsoever in decisions, and were required to do most, if not all, of the work. Historically, men would pull the front teeth of their wives to signify ownership, and more recently, the government has capped the amount a man must pay the family of his wife-to-be for the privilege of marriage.

I mentioned that I had seen a woman managing the local bank (we had to change money), and he allowed as to how in the workplace, women could occupy management, but once back in the village and the home, the man was in charge. Sitting beside him a strikingly- beautiful, well-dressed woman nodded her head in supportive agreement. By then, our conversation had become friendly enough that I felt comfortable smiling and tossing a small pebble at his feet, as he sat across the way on a similar bench. "Pretty good deal for the men, no?" He smiled, and said it's always been that way and would always be that way.

Later, as we bumped and rolled our way back to the village, we spied dozens of women walking along the rutted road, carrying loads of firewood, baskets of yams, and swatting flies and mosquitoes. One step and then another, after a day collecting fuel for the evening's cook fire, food for the family. Nothing romantic here; mud-splattered clothes, tired eyes, and a pervasive sense of just another day in a subsistence world.

The next day, as we toured the village with Stanley, and on our way to the white sand beach, we passed through a compound of unwalled, roofed shelters, each with rough-hewn benches under the cover. This was the man's compound, where each day, in the late afternoon, the men of the village would gather and drink kava, the slightly narcotic drink that is made from the roots of a local pepper plant. No women are allowed; Stanley explained that this is where the men gathered daily to talk, discuss, and resolve any issues or problems arising in the village. Back in the village, the women would be cleaning the dishes, washing the clothes, and putting the children to bed.

The village we were fortunate enough to visit had several graves surrounded by rusted wrought iron fence stakes; one commemorated a missionary who had died in 1893, well after Captain Cook arrived. After several unsuccessful attempts to land (many were murdered by the natives), the missionaries finally established footholds in many of the islands that were then called the New Hebrides (Vanuatu became independent in 1980). However, these missionaries were unable to stem one of the more reprehensible practices of Europeans - the so-called "blackbirding," where unscrupulous merchants kidnapped natives by the thousands to provide cheap (slave) labor in the booming sugar, banana and coconut plantations in Fiji, Tonga, and elsewhere. To combat this, both the French and English governments sought to police the islands of Vanuatu, and, eventually and unworkably, formed a "condominium" government, with each foreign power establishing its own government, schools, courts, etc. To this day, many ni-Vanuatu speak at least four languages: the local village tongue (several hundred dialects); Bislama - a curious pidgin English; proper English, and French. Tragically, until independence, each European government tended to look only after its own citizens. Only the missionaries saw fit to focus on the locals. Thus, a deeply religious people, and a curiously strong mix of Biblical literalism coupled with pre-European cultural traditions.

Stanley is building a new house, one with a small 7x7 foot "room" for his daughter, Naomi. He does not have a first son, and seems not to have any immediate plans for more children. We never met his wife, although we did meet his sisters and brother. As we left, he was walking over to the kava huts. Smoke seeped out from the huts dedicated to cooking, and women were walking back from the jungle, with large bundles of sticks on their shoulders. The kids were gathering for the afternoon soccer game, having just joined the school's elders in a traditional dance celebrating the completion of exams and thanking the teachers for their service. Around the perimeter of the bay, steam wafted from volcanic vents, and the volcano's ash cloud covered the western sky. We settled down for a dinner of Indonesian rice and chicken, and the nightly rains began to fall.

We are headed to Cairns, Australia in the morning, a 1400 mile trip that should take 12 days. On reflection, after a week in Tanna, each sea-going mile seems like it could just as easily take a month, our voyage as a whole passing through 1400 months of native, colonial, and post-colonial history, stretching back 117 years to the year 1893, when the people of Ireupuow buried the last "first" missionary and began their ever-so-gradual process of reconciling the European views of culture with their native traditions. Chief Stanley has his hands full; we wish our new friend well, and cannot help but wonder if there will be a second son to carry on his duties when Stanley eventually joins his father, Chief Ronnie, in the afterlife.

And the women - the girls we saw in the village school; the daughter of the well-dressed woman in Lenakel; Naomi - what will become of the women of Vanuatu?