Saturday, December 25, 2010

Merry Christmas From Down Under

On arrival, as faithful readers may recall, we first unloaded all the U.S.-acquired supplies for the boat, notably a replenishment of our declining supplies of the powdered drink mix Crystal Light, my primary food group. Thanks Kate! David schlepped the essential boat supplies.

The weather -- notably the accompanying wind -- prevented us from sailing to a local island for Christmas, but we had a wonderful time at the dock preparing and eating a tasty Christmas eve Middle Eastern dinner of lamb, eggplant, and chicken kabobs. The rain continued all night, and after a Christmas morning breakfast and gift sharing, we set off to the mountains that surround this coastal city, hoping to see some of the spectacular waterfalls at full strength.

We made it about 5 km inland before being stopped by a road crew, who informed us that there was 15 feet of water overflowing the road up ahead. The roads here are few and far between, and it would have been a 100 km roundabout to get to the other side of the flood -- so we turned around, headed north, and made it to Kurunda, site of the famous Barrons River Gorge, a massive falls whose incoming roads were free of floods.

A spectacular sight, made all the nicer by the clearing of the skies. We returned to Cairns, spent some time picnicking at the freshwater, manmade lagoon that adjoins the harbor here, and are now settling in to a Christmas dinner of scallops, shrimp, and a "bug" salad, "bugs" being the local name for a small lobster that is quite the rage here in Oz.

Merry Christmas to all!

Sunday, December 12, 2010

Runes

We've also had the chance to make a few visits to the doctors and dentists, taking care of some of the routine health matters that accumulate as one drifts across ocean waters and isolated islands. All is well for each of us thankfully, but it did get me thinking about the aging process. As good as I feel, I do notice that I'm getting older in body and -- perhaps I'm wrong here, wiser in mind, as if there was a yin and yang to these two trends. If so, I'm happy for it: perspective, resilience, discernment -- I'm happy trading some creaky joints and loose skin for these traits.

I've tried to capture this below, in a new poem, titled Runes. In it, I tried to have each line read logically as a stand-alone line, even as they connect to form a larger image, the whole being greater than the sum of our parts, as it were.

Friday, December 10, 2010

Under the Sea

Unfortunately, this posting does not have pictures to accompany it because Jon and I do not have an underwater camera. Shameful, I know, but an expensive proposition. From past diving experiences, we never got any good photos off the disposable underwater cameras, and we also found that focusing on photography really distracted us from fully enjoying the experience of being underwater.

This lack of pictures, however, has inhibited me from writing about our underwater experiences. But truly, they have included some of the more memorable, more magical, and more otherworldly experiences of our adventure. They say a picture paints a thousand words, but in this case, even a picture cannot fully convey the experience of being under the sea. Nevertheless, here’s my feeble effort.

We first wiggle ourselves into neoprene wet suits, don heavy BCD’s (buoyancy control devices) attached to heavy air tanks, strap weights around our waists, put on huge flippers and top ourselves off with big googley-eyed masks. We couldn’t look goofier nor move less gracefully if we tried. (Photos of this are possible, but I have some pride!) Quickly, however, we roll backward off the edge of the dive boat and we are in another world for about 40 minutes.

Initially, the loss of noise seems stark, but we quickly adjust to the sound of our own breathing as each inhale sounds like a spaceman’s and each exhale sends gurgling bubbles that look like jellyfish back up to the surface. As we descend, clearing the pressure from our ears and feeling the pressure squeeze our masks tighter to our faces, a new sound emerges: the crackling popping sound of live coral. Coral is a live animal, but it’s hard to believe. In Vava’u, Tonga, another sound caught our attention at about 40 feet underwater; a male humpback whale singing in the far distance.

After the descent, we get the lay of the land. Reefs have similar attributes, but each also has its own topography. Often, we begin on a flat plateau, which is the top of the coral reef, and descend along the edge to what is called a wall. These often descend in a stair step manner. Imagine a mountain that’s ¾ underwater; the ¼ above the water is the island, but the rest tapers down gently. There are also chasms underwater. Coral does not grow in fresh water, so a river or spring flowing into the reef creates channels that make for fun exploring. The island of Niue is an uplifted coral atoll, not a volcanic mountain, and has a large underground water aquifer stored in its limestone foundation, with many fresh water springs along its shore. There the many chasms and caves created mazes of reef that we explored only with a local guide.

Rarotonga, like many South Pacific islands, has a large, flat and shallow lagoon on its southern side, which made for fun snorkeling. A lagoon is the area between the island and the reef that surrounds it. After first being treated to a 10-minute show by a breeching humpback whale, we dove this reef, which, instead of having a stair stepping wall, the edge of the reef had a 2,700-foot cliff! As an acrophobic, if I were on land, I would be well clear of the edge of such a cliff. But under water, I hovered over it, peacefully, calmly and grinning from ear to ear. Not just along the edge, but actually pretending to be a hawk or and an eagle floating on an air stream well over the edge and looking down into a bottomless abyss.

The visibility has been amazing throughout the South Pacific. Visibility in water can be affected by choppy water stirring up sand and by run off from land. On coral atolls, this is not so much a problem. Many islands are small and have no rivers or streams for run off. They also often have coralline shores rather than sandy shores. The result is crystal clear water where one can see clearly up to 40-50 meters and 70 meters is not unheard of! When snorkeling off the outer reef in the Tuamotus, looking though 30 meters of sea was like looking through air on a clear day.

Then there’s the coral itself. The diversity has been amazing. In addition to the familiar brain and elk horn corals, we’ve enjoyed seeing red and purple fan corals, soft corals, and multi-colored corals. As a gardener, it’s difficult for me to look as them as animals and not exotic plants. Some grow out in semi-circular plates and look a bit like fungus you’d find in a dark woody forest. One type grows like a twig; no branches, just one long thin twig that sways in the current. The colorful ones often grow in clumps; a favorite of mine grows a mound of light brown stalks with robin’s egg blue at the tips. In Fiji, we saw small mounds of soft white coral, the color of ground chalk, but swaying in the current. And, it is impossible for me not to get excited when I see anemones. A soft coral, their pinkish soft tubes sway in the currents with their mouths in the center opening and closing as food passes by. We saw our first one in Niue and then again in Tonga and Fiji. In addition to being more animal like, they are home to anemone fish, otherwise known as Nemo.

Finally, there are the fish. Colorful little tropical fish, which dart up quite close but always manage to evade the hand that is tempted to touch them, include a myriad of angels, triggerfish, tangs, unicorns, butterfly fish, and sergeant majors to name just a few. Trumpet fish and flute mouths skim the surface while parrot, squirrel, hawk, and groupers cruise the bottom. Creepy eels, lionfish and octopi like to hide but are easily espied under rocks and behind crevices. Sea turtles are also fun to watch, but they don’t seem too interested in us---we’re not food. Fortunately, I’ve never seen the poisonous stonefish whose venom is a powerful neurotoxin and can kill you within 20 minutes of a sting. Unfortunately, I also have never seen a sea horse, but I keep my eyes out for one. Starfish and sea cucumbers appear static on the bottom, but I’ve read they move in herds.

And of course, there are the reef sharks. At first, I was afraid to be with sharks underwater, but I have come to learn that reef sharks are not very aggressive; they hunt at night, and do not find us humans particularly interesting. Still, I have no desire to provoke them, and follow the local wisdom of “leave them alone and they’ll leave you alone.” It’s their world and they are at the top of the food chain. I am just a brief interloper, as alien to them as they are to me. The same goes for the sting rays and lovely manta rays.

By far, however, sea mammals offer the most exciting experience. Whales and dolphins offer a kind of kinship with their intelligence, playfulness and ability to communicate. They permit us to be in their presence; and, considering that some of mankind has wanted to hunt them into extinction and to pollute and corrupt their oceanic habitats, they are actually quite tolerant of us. When I have had the chance to encounter these magnificent animals, I am overwhelmed by the sense of respect I feel for them. And I am thankful they were willing to share the water with me for a few moments.

It all makes me feel quite fortunate. I don’t take for granted that I’ll always be able to dive under the sea. It is a serious and technical endeavor, a privilege that can be lost for the slightest of health reasons. But as long as I am able to dive, I will be grateful for each opportunity, knowing that each submersion offers a brief glimpse into the alien world that comprises most of our planet.

Now, Jon and I are anchored a few kilometers off the Great Barrier Reef of Australia; one of the seven natural wonders of the world. We are waiting for the arrival of Katie and her boyfriend Dustin, and David and his fiancé Marisa for Christmas so we can all enjoy a couple of dives together. Maybe we’ll even try a night dive.

Sunday, November 21, 2010

New Posts

Saturday, November 20, 2010

Passage to Cairns, Australia

We were escorted from Tanna's shores by spinner dolphins. About a dozen were cruising past our starboard side heading east, as we were heading west. When they were abeam, they turned in unison toward our bows. It's always thrilling to have company at sea. Given our lack of a common language to get the full scoop, we can only speculate that they are familiar with fishing boats and perhaps were hoping we'd have fish for them. But I like to think they also are curious about us and enjoy frolicking in the bow wakes. Jon and I sat on the bow seats and enjoyed their show. They stayed for half an hour and then were gone.

We were escorted from Tanna's shores by spinner dolphins. About a dozen were cruising past our starboard side heading east, as we were heading west. When they were abeam, they turned in unison toward our bows. It's always thrilling to have company at sea. Given our lack of a common language to get the full scoop, we can only speculate that they are familiar with fishing boats and perhaps were hoping we'd have fish for them. But I like to think they also are curious about us and enjoy frolicking in the bow wakes. Jon and I sat on the bow seats and enjoyed their show. They stayed for half an hour and then were gone. Our other visitors are sea birds. On this passage a noddy (we think) decided we were a cool place to rest from its never-ending quest for fish. It was the first time a bird landed on board (at least that we know of) at sea and stayed for a while. He slept on our outboard engine for one of my four hour watches. Like I said, it's fun to have company at sea, but this guest left his droppings.

Our other visitors are sea birds. On this passage a noddy (we think) decided we were a cool place to rest from its never-ending quest for fish. It was the first time a bird landed on board (at least that we know of) at sea and stayed for a while. He slept on our outboard engine for one of my four hour watches. Like I said, it's fun to have company at sea, but this guest left his droppings. Other regular visitors on this passage were blue-beaked boobies. This one hung around our boat a lot, but never got the courage to land. At times he was joined by 6 or 7 other boobies, circling our boat, probably looking for fish. They are beautiful birds and their surfing along the the tops of waves is a sight to see. Still, I am glad I do not have to make my living as a sea bird....it's a long time away from home and the rewards of hunting seem few and far between.

Other regular visitors on this passage were blue-beaked boobies. This one hung around our boat a lot, but never got the courage to land. At times he was joined by 6 or 7 other boobies, circling our boat, probably looking for fish. They are beautiful birds and their surfing along the the tops of waves is a sight to see. Still, I am glad I do not have to make my living as a sea bird....it's a long time away from home and the rewards of hunting seem few and far between. Our second day out, Jon the fish slayer could not help himself and put two fishing lines out. Though we were not in need of food and I was off watch, I was awoken by an excited "Jen!!!" which meant he had a fish on the hook. He promised me if it was a mahi-mahi, he'd throw it back. (I've gotten a little tired of fish lately, and we were trying to eat up what meats we had remaining before we arrived in Australia.) Luckily for Jon, but not for the fish, it was a short-billed spearfish; Jon was so happy with his non-mahi-mahi catch that it was impossible to stay irked for long. Besides, who can be annoyed at a man who goes deep sea fishing in his boxers?

Our second day out, Jon the fish slayer could not help himself and put two fishing lines out. Though we were not in need of food and I was off watch, I was awoken by an excited "Jen!!!" which meant he had a fish on the hook. He promised me if it was a mahi-mahi, he'd throw it back. (I've gotten a little tired of fish lately, and we were trying to eat up what meats we had remaining before we arrived in Australia.) Luckily for Jon, but not for the fish, it was a short-billed spearfish; Jon was so happy with his non-mahi-mahi catch that it was impossible to stay irked for long. Besides, who can be annoyed at a man who goes deep sea fishing in his boxers? Besides, the fish really tasted good!

Besides, the fish really tasted good! In addition to lovely meals, we enjoyed lovely sunsets and sunrises as seen here. We were able to read to our hearts' content, get plenty of rest, and clean the anchor locker and chain before our arrival. All in all it was a great 12 day passage and the longest one Jon and I have made just the two of us thus far.

In addition to lovely meals, we enjoyed lovely sunsets and sunrises as seen here. We were able to read to our hearts' content, get plenty of rest, and clean the anchor locker and chain before our arrival. All in all it was a great 12 day passage and the longest one Jon and I have made just the two of us thus far. Finally, on Tuesday, November 16th, with the mountainous coastline of Queensland in sight, Jon hoisted the flags of all the countries we've visited this year on the port side, the Australian and Quarantine flag on the starboard, and of course, the Stars and Stripes flew proudly off the stern.

Finally, on Tuesday, November 16th, with the mountainous coastline of Queensland in sight, Jon hoisted the flags of all the countries we've visited this year on the port side, the Australian and Quarantine flag on the starboard, and of course, the Stars and Stripes flew proudly off the stern. The Fury of Mt. Yasur

Today we were going to pack in a visit to a Kastom Villlage and a trip to the Volcano, Mt. Yasur in the evening, but after yesterday's jarring and long road trip to Lenakel, we did not have the stamina for another all day road trip. I don't think the drivers of the village's truck (Robeson and Mr. John) were up for it either. So it was only to be a visit to the volcano for us.

Today we were going to pack in a visit to a Kastom Villlage and a trip to the Volcano, Mt. Yasur in the evening, but after yesterday's jarring and long road trip to Lenakel, we did not have the stamina for another all day road trip. I don't think the drivers of the village's truck (Robeson and Mr. John) were up for it either. So it was only to be a visit to the volcano for us. Locals believe that Mt. Yasur (which means Old Man) is the originator of the universe and the place where souls go after death. Followers of the John Frum religion (see Jon's earlier post, Sons and Daughters) believe that Frum and his army live in the volcano. After my first encounter, it was easy to understand how primitive people who lacked the knowledge of science could believe that gods resided in volcanos, displaying their power, fury and mercy. For me, the actual geology is more accurate and more exciting, but, given that our science indicates the Earth was formed by the Sun's gravitational pull on the primordial gases and debris from the Big Bang, perhaps their religion isn't too far off after all.

Locals believe that Mt. Yasur (which means Old Man) is the originator of the universe and the place where souls go after death. Followers of the John Frum religion (see Jon's earlier post, Sons and Daughters) believe that Frum and his army live in the volcano. After my first encounter, it was easy to understand how primitive people who lacked the knowledge of science could believe that gods resided in volcanos, displaying their power, fury and mercy. For me, the actual geology is more accurate and more exciting, but, given that our science indicates the Earth was formed by the Sun's gravitational pull on the primordial gases and debris from the Big Bang, perhaps their religion isn't too far off after all.  While the intensity of its activity can fluctuate, the volcanic activity pretty much runs 24/7. We smelled the sulfur and heard the gurgling well well before we could see any signs of molten rock shooting skyward. The volcano has 3 vents which erupt in rock and smoke. When I first heard the largest vent blow, I nearly jumped out of my skin at the deep earth-splitting sound and the shuddering I felt beneath my feet. Our guide was one of Stanley's younger brothers. He laughed and seemed quite at ease with the seeming fury occurring below us. After an eruption, the Earth seemed to gasp for air and then calm briefly. The volcano let us see our planet as a dynamic, breathing entity recycling itself to sustain life, which geological time does not often let us appreciate.

While the intensity of its activity can fluctuate, the volcanic activity pretty much runs 24/7. We smelled the sulfur and heard the gurgling well well before we could see any signs of molten rock shooting skyward. The volcano has 3 vents which erupt in rock and smoke. When I first heard the largest vent blow, I nearly jumped out of my skin at the deep earth-splitting sound and the shuddering I felt beneath my feet. Our guide was one of Stanley's younger brothers. He laughed and seemed quite at ease with the seeming fury occurring below us. After an eruption, the Earth seemed to gasp for air and then calm briefly. The volcano let us see our planet as a dynamic, breathing entity recycling itself to sustain life, which geological time does not often let us appreciate. It was so cool. Not hard to understand why they let you send post cards from there. By 7 we were headed back to the village along the jarring roads and once again arrived at our boat both exhausted and thrilled. Having visited volcanic islands across the Pacific, it was rewarding to actually see one in the process of doing its thing. It was an unforgettable experience and one I'd repeat if ever given the opportunity.

It was so cool. Not hard to understand why they let you send post cards from there. By 7 we were headed back to the village along the jarring roads and once again arrived at our boat both exhausted and thrilled. Having visited volcanic islands across the Pacific, it was rewarding to actually see one in the process of doing its thing. It was an unforgettable experience and one I'd repeat if ever given the opportunity.A Long Day's Journey Into Dusk

We arrived in Port Resolution Harbor yesterday around 10 am, fully expecting to have the rest of the day to clear in. Lonely Planet said it was only 41 kilometers to the customs and immigration offices in Lenakel (about 25.5 miles). Our passage from Fiji was only 4.5 days, so after a bit of tidying up, we thought we'd go ashore, dash over to Lenakel, and come back for dinner. No sooner were we anchored than a steady rain began. Neither Jon nor I felt much like leaving our boat and getting soaked, so we waited a few hours. By early afternoon, Jon rowed ashore to the Yacht Club, which our cruising guide indicated was the first point of contact for sailors wishing to clear in, and met Werry, the Club's manager. "Oh, no. It's too late to go to Lenakel today," he said. "Come back tomorrow morning around 6:30 (a.m.)."

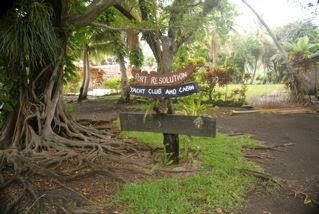

We arrived in Port Resolution Harbor yesterday around 10 am, fully expecting to have the rest of the day to clear in. Lonely Planet said it was only 41 kilometers to the customs and immigration offices in Lenakel (about 25.5 miles). Our passage from Fiji was only 4.5 days, so after a bit of tidying up, we thought we'd go ashore, dash over to Lenakel, and come back for dinner. No sooner were we anchored than a steady rain began. Neither Jon nor I felt much like leaving our boat and getting soaked, so we waited a few hours. By early afternoon, Jon rowed ashore to the Yacht Club, which our cruising guide indicated was the first point of contact for sailors wishing to clear in, and met Werry, the Club's manager. "Oh, no. It's too late to go to Lenakel today," he said. "Come back tomorrow morning around 6:30 (a.m.)." OK. No worries. Except that we did not know that we did not know what time it was in Vanuatu. Despite charts, a time map, and electronic equipment out the wazoo, sometimes it's hard to know exactly what time it is in a new country when you're on a boat, given that daylight savings times are particular to each county ... some actually adjust their times in 30 and 15 minutes increments ... and given that being at sea probably addles my brain a bit. Needless to say, after thinking we were running late, we arose too early, arrived at the yacht club at 5:30 local time, and patiently waited for Werry to awaken. As you can see, the Yacht Club is sparse, but charming. Its open air walls let in a fresh breeze, we found familiar boats in the registry, and enjoyed checking out the various burgees from yachts and yacht clubs around the world.

OK. No worries. Except that we did not know that we did not know what time it was in Vanuatu. Despite charts, a time map, and electronic equipment out the wazoo, sometimes it's hard to know exactly what time it is in a new country when you're on a boat, given that daylight savings times are particular to each county ... some actually adjust their times in 30 and 15 minutes increments ... and given that being at sea probably addles my brain a bit. Needless to say, after thinking we were running late, we arose too early, arrived at the yacht club at 5:30 local time, and patiently waited for Werry to awaken. As you can see, the Yacht Club is sparse, but charming. Its open air walls let in a fresh breeze, we found familiar boats in the registry, and enjoyed checking out the various burgees from yachts and yacht clubs around the world. We left the village of Ireupuow around 7 am in a small four wheel pick-up truck, driven by Robeson with Mr. John riding shotgun. Jon, Mark (a 17 year old who went to school in Lenakel) and I were in the back seat of the cab. And huddled together back in the bed of the truck were 10 more villagers hitching a ride into town. It quickly became apparent that this was not going to be as quick of a trip as we thought. The roads were unpaved, narrow, and full of deep, rain-riven gullies which had to be carefully navigated by Robeson----and we discovered that Mr. John's role on the passenger side was to let Robeson know exactly how much room he had to spare on the left hand side. We bounced from side to side into each other and held on tight as we listened to the laughter and screams from the passengers behind us, sitting on narrow wooden slats, and to the 1970s and 80s pop music coming out of the cab's CD player. Soon, there was no road at all as we crossed the ash plain created by the volcano at Mt. Yasur.

We left the village of Ireupuow around 7 am in a small four wheel pick-up truck, driven by Robeson with Mr. John riding shotgun. Jon, Mark (a 17 year old who went to school in Lenakel) and I were in the back seat of the cab. And huddled together back in the bed of the truck were 10 more villagers hitching a ride into town. It quickly became apparent that this was not going to be as quick of a trip as we thought. The roads were unpaved, narrow, and full of deep, rain-riven gullies which had to be carefully navigated by Robeson----and we discovered that Mr. John's role on the passenger side was to let Robeson know exactly how much room he had to spare on the left hand side. We bounced from side to side into each other and held on tight as we listened to the laughter and screams from the passengers behind us, sitting on narrow wooden slats, and to the 1970s and 80s pop music coming out of the cab's CD player. Soon, there was no road at all as we crossed the ash plain created by the volcano at Mt. Yasur. This non-road, led to a rain-swollen river with a non-bridge. Because of the rains from the day before, the river, -- a dry bed in the winter (our summer) -- was running about 2-2.5 feet deep. It was not to be crossed without the general agreement of Chief Stanley, Robeson and Mr John. After testing and consultation, we waited an hour and a half for the waters to recede a bit. This gave us time to meet our fellow travelers and to stare in awe at what a volcano can leave in its wake. The sky was overcast, from the precipitation as well as from the ash that spews daily from the nearby volcano's caldera. In addition, the landscape was filled with mini canyons, created by the river as well as from past lava flows. It felt otherworldly--a bit like a desolate moonscape.

This non-road, led to a rain-swollen river with a non-bridge. Because of the rains from the day before, the river, -- a dry bed in the winter (our summer) -- was running about 2-2.5 feet deep. It was not to be crossed without the general agreement of Chief Stanley, Robeson and Mr John. After testing and consultation, we waited an hour and a half for the waters to recede a bit. This gave us time to meet our fellow travelers and to stare in awe at what a volcano can leave in its wake. The sky was overcast, from the precipitation as well as from the ash that spews daily from the nearby volcano's caldera. In addition, the landscape was filled with mini canyons, created by the river as well as from past lava flows. It felt otherworldly--a bit like a desolate moonscape.

We arrived in Lenakel around 11:30, averaging just over 5 and a half mph in what Jon referred to in his Sons and Daughters post as a "bone jarring" ride. It was clear that "going to town" was not easy and whatever business we planned to get done while in Vanuatu had to be done that day. First to the bank for Vatu (money) and then to lunch because customs and immigration were also out to lunch and we had to wait until one.

We arrived in Lenakel around 11:30, averaging just over 5 and a half mph in what Jon referred to in his Sons and Daughters post as a "bone jarring" ride. It was clear that "going to town" was not easy and whatever business we planned to get done while in Vanuatu had to be done that day. First to the bank for Vatu (money) and then to lunch because customs and immigration were also out to lunch and we had to wait until one. Lunch was chicken and rice in a small cafe on main street (see photo above) and Stanley joined us. I thought clearing customs and immigration was something Jon and I were doing on our own, as we've done everywhere else, but it began to dawn on me that Stanley was along for the ride as our escort. His father had helped get Port Resolution on the list of permissible places for cruisers to enter, but it's not really a port; it's a harbor with a village. Without confirming this, I suspect that he accompanied us to vouch to the officials that we were indeed in his harbor, had indeed just arrived, were who we said we were, and hadn't gone anywhere else before checking in.

Lunch was chicken and rice in a small cafe on main street (see photo above) and Stanley joined us. I thought clearing customs and immigration was something Jon and I were doing on our own, as we've done everywhere else, but it began to dawn on me that Stanley was along for the ride as our escort. His father had helped get Port Resolution on the list of permissible places for cruisers to enter, but it's not really a port; it's a harbor with a village. Without confirming this, I suspect that he accompanied us to vouch to the officials that we were indeed in his harbor, had indeed just arrived, were who we said we were, and hadn't gone anywhere else before checking in. After lunch and needing a nap, Jon went to deal with the official clearing in, and I went to manage our affairs, check in with family and mail post cards. To the left of the internet cafe is the bank (it has no ATM) and inside the bank is the Post Office (the teller at the end) and next door to the right was the small grocery, sparsely stocked much like an old Soviet era store. Sitting on a bench outside the internet cafe (see left), watching the comings and goings of this small village, I was struck by how physically removed I felt from modernity and yet I was conducting wireless online banking and video chatting with our daughter Kate. When Jon arrived, he reminded me that we were required to send an email to Australian Customs and Quarantine prior to our arrival....so off the email went and then it was back in the truck for the return trip to Ireupuow.

After lunch and needing a nap, Jon went to deal with the official clearing in, and I went to manage our affairs, check in with family and mail post cards. To the left of the internet cafe is the bank (it has no ATM) and inside the bank is the Post Office (the teller at the end) and next door to the right was the small grocery, sparsely stocked much like an old Soviet era store. Sitting on a bench outside the internet cafe (see left), watching the comings and goings of this small village, I was struck by how physically removed I felt from modernity and yet I was conducting wireless online banking and video chatting with our daughter Kate. When Jon arrived, he reminded me that we were required to send an email to Australian Customs and Quarantine prior to our arrival....so off the email went and then it was back in the truck for the return trip to Ireupuow. While waiting for others who also were returning to Ireupuow, Jon took this photo of a sign in Bislama, more commonly known as pidgen English. You can figure it out. There were also signs regarding public health and HIV. It was fun to decipher and even more fun to hear. Vanuatu has over one hundred native languages spoken in its archipelago (due to the isolation of villages and islands from each other), but 3 languages are official: Bislama, English and French. This being the result of colonization and the rare Condominium of joint French and English rule.

While waiting for others who also were returning to Ireupuow, Jon took this photo of a sign in Bislama, more commonly known as pidgen English. You can figure it out. There were also signs regarding public health and HIV. It was fun to decipher and even more fun to hear. Vanuatu has over one hundred native languages spoken in its archipelago (due to the isolation of villages and islands from each other), but 3 languages are official: Bislama, English and French. This being the result of colonization and the rare Condominium of joint French and English rule. The return trip did not entail a wait at the river, and only took us 2 and a half hours to go 25.5 miles. It was still bumpy, and the deeply muddy road that we slid down coming into Lenakel was much more difficult to ascend. We skidded all over the narrow road, wheels spinning, mud flying, women laughing in a recurring kind of joyous screaming. Robeson's skills were beyond doubt, but eventually his luck ran out and we got stuck at a place where the entire road seemed to veer right into a gully. Everyone got out, and out of the way, as he ground the gears, burned the clutch and rocked the truck free.

The return trip did not entail a wait at the river, and only took us 2 and a half hours to go 25.5 miles. It was still bumpy, and the deeply muddy road that we slid down coming into Lenakel was much more difficult to ascend. We skidded all over the narrow road, wheels spinning, mud flying, women laughing in a recurring kind of joyous screaming. Robeson's skills were beyond doubt, but eventually his luck ran out and we got stuck at a place where the entire road seemed to veer right into a gully. Everyone got out, and out of the way, as he ground the gears, burned the clutch and rocked the truck free. Interestingly, there was a group of people roasting bananas on the side of the road where we got stuck. Surely we, and the other trucks that had passed that way, were the afternoon's entertainment. In any event, they were not surprised at our predicament and did not seem too concerned that we wouldn't soon be back on our way. Along the way, Robeson delivered a package to a school, dropped a few people off early, and meandered back into Ireupuow as dusk was encroaching on the day. Our mission of clearing in had been accomplished. It had been an unexpectedly adventurous and wonderful day. But even a long passage at sea had not left us as completely exhausted as we were by the time we hiked back down the trail to our dinghy, puttered back to Grace, peeled our muddy clothes and shoes off in the cockpit and collapsed into bed.

Interestingly, there was a group of people roasting bananas on the side of the road where we got stuck. Surely we, and the other trucks that had passed that way, were the afternoon's entertainment. In any event, they were not surprised at our predicament and did not seem too concerned that we wouldn't soon be back on our way. Along the way, Robeson delivered a package to a school, dropped a few people off early, and meandered back into Ireupuow as dusk was encroaching on the day. Our mission of clearing in had been accomplished. It had been an unexpectedly adventurous and wonderful day. But even a long passage at sea had not left us as completely exhausted as we were by the time we hiked back down the trail to our dinghy, puttered back to Grace, peeled our muddy clothes and shoes off in the cockpit and collapsed into bed.Thursday, November 18, 2010

Update

Friday, November 12, 2010

Blue Planet

With a following wind, astride the twin hulls of our catamaran, I feel like a kid on skis, being pulled by a giant kite across a lake so big it defies the imagination. The boat rocks back and forth slightly, the hulls dipping and rising, the bow lifting and then the stern as the folowing waves pass beneath us. Jennifer is asleep below; we're on a 4-on, 4-off watch system, and sleep comes quickly for both of us. We've been lucky on this passage, and we've been lucky on our entire voyage from Panama - we've almost always had the wind on our back, taking advantage of the trade winds that flow southeast to northwest in these subtropical southern latitudes. They say that gentlemen never sail upwind, and while my clothes and behavior might suggest otherwise, I am now proud to call myself a gentleman.

As the petrels and terns might fly, it's about 9,300 statute miles from Panama to Cairns, a huge sweeping great circle arc across the small scale chart I have on the boat. When we left Panama in early February, bound for the Galapagos and islands beyond, I had an intellectual appreciation of the Pacific Ocean's breadth. On many maps of the world generated for US schools, North America is centered on the page, leading to a classically distorted view of global geographic distances and perspectives. As we've sailed each of those 9,300 miles (and more, given our meanderings),and knowing that the Pacific Ocean extends roughly 7,500 miles north-to-south, I am reassured that there is a unfathomable volume of water and open space on this planet that keeps everything we do, individually and as a species, in perspective. Do the math: over 64 million square miles of ocean - larger than all of the land masses of the planet put together. All water all the time, in places 7 miles deep. We're a small boat on a big ocean.

In chemistry, there's a thermodynamic concept known as a "heat sink," an ideal abstraction of a material capable of absorbing all of the energy (heat) of a given chemical reaction. Such a concept simplifies the mathematics of examining these reactions, which tend to produce or require heat. In essence, a heat sink absorbs energy. The Pacific Ocean, integral to our global weather patterns through such well-studied phenomena as La Nina and El Nino, serves as a global climatologic heat sink, absorbing and emitting solar energy, fueling jet stream wind patterns, and supplying moisture for rain and clouds.

I have a different view of the Pacific Ocean's heat sink-like attributes capabilities, one more geared to its constant reminder that humankind may come and go, our institutions rise and fall, our foibles and magnificence wax and wane, but still the waters of this magnificent ocean will churn under a distant sun. I receive a brief weekly update on Washington DC's political machinations from a friend, and while they briefly arouse emotions of outrage, disappointment, and (very occasionally, optimism), I am sailing across my own personal heat sink where they rapidly dissipate. Even, truth be told, I am losing the tight emotional connection to the people, organizations, and communities I've left behind, both as a result of less interaction, but also, because this ocean has become a reservoir and reminder of deeper cycles and rhythms.

This letting go of things that once mattered dearly to me is not without precedent. However, this time, the letting go has been a more gradual transformation than the ones I recall occurring during my younger stints at sea. I first spent a year at sea, when I was just 20 years old. Then, I had completed my sophomore year at college, and needed to get away from a US Navy scholarship that threatened to choke my sense of independence (even as it paid for two years of education), and to realize that I might be happier in a world of ideas and politics than in a world of equations and science. I returned from that year committed to pursuing international studies and a more liberal arts education at the decidedly-science oriented university I eventually graduated from. After another year at sea at the age of 23, I returned to enter graduate school, changed my career interests to domestic studies and economics, met my not-so-future and still-present wife, and spent the following 25+ years creating and raising a family, working, and, sometimes painfully, coming to a clearer understanding of who I am and what I want.

Time and circumstance and good luck coincided in 2009 to let me undertake yet this third and more extensive sea voyage, this time with my best friend and partner of nearly 30 years, a voyage whose first leg is almost complete. Now, nearly a year in, I have begun to feel that earlier-experienced sense of letting go, a release that seemed to arise more quickly in those earlier voyages. We age, and our bodies and minds are less supple, becoming both less vulnerable and more resistant to the changing weather patterns around us. I don't mind this hardening of the soul; it takes more to move me these days, but once moved, I find the new places all the more rewarding. There's more to let go, and it's harder to separate the wheat from the chaff. At night, when my watch is over, I lie in bed reflecting on friends I've lost along the way, ideas I've left on the table, paths not taken. I mull over things I've done and not done, words said and unsaid. No real regrets, but lots of reflective learning: what's central and what's peripheral. At the age of 53, any letting go seems far more consequential than the larkish asides of my 20s. No clean answers this time around; that's the stuff of fiction and fairy tales. Nightly reflection, on an ocean rippled with phosphorescence and the white water of breaking wave tops, is probably the best I'll muster.

But I can say this: I dearly miss my immediate family, my closest friends, the mighty challenges of helping to guide people and organizations to common goals, and my day-to-day human interactions with smart, compassionate, curious souls. But here, on a small boat, on a big sea, with petrels and terns gliding and swooping inches above the waves, with the sinking moon backlighting the clouds atop the western horizon, I am grateful for this mighty ocean's ability to absorb the manmade noise and clutter of our daily lives, to serve as an emotional heat sink for our passing follies and fancies, and to remind us of our transient existence on this planet - this blue planet --- we call home.

Our families, our workplaces, our communities surely define us as human beings, but here, tonight, heading downwind under a starry sky, they are juxtaposed against an ocean, a world and a universe that moves to its own winds, its own currents, its own forces. Little things, little problems, little issues - they will all pass; other things matter deeply, profoundly. The trick is giving oneself the space and time to decide which is which, away and apart from the noise and clutter of a world that tries to make everything matter.

For me, the central insight of this voyage might be this: It's not that nothing matters; it's that very few things matter, and that it's well-nigh impossible to tell the difference between what matters and what doesn't without leaving everything behind for awhile and being reminded of our passing insignificance by a massive ocean, a limitless sky, and the space and silence to reflect without distraction.

We arrive in a few days, to a new land and new experiences and, yes, clutter and noise. Perhaps, instead of asking this ocean to absorb the clutter, I'll begin to draw from it the peace and tranquility needed to maintain a sense of balance and perspective as we spend 4 months living ashore. I do know this: my son and daughter arrive in a month to spend a week with us. What can matter more than that?

--Jon Glaudemans

Tuesday, November 9, 2010

Australia Bound!

Monday, November 8, 2010

Sons and Daughters

The village of Ireupuow lies atop a promontory overlooking Port Resolution, one of the many natural harbors "discovered" by the incomparable Captain James Cook, who practically invented the South Pacific. At the time Cook's ship "Resolution" made its way into this large cove surrounded by jungle vegetation, steaming volcanic vents, and natural hot springs, the bay was much deeper than it is today. A series of earthquakes and tremors have since raised the sea bed so that today it lies just 3-4 meters below the surface. We arrived at first light on a Monday, after a 4.5 day passage from Fiji.

The village of Ireupuow lies atop a promontory overlooking Port Resolution, one of the many natural harbors "discovered" by the incomparable Captain James Cook, who practically invented the South Pacific. At the time Cook's ship "Resolution" made its way into this large cove surrounded by jungle vegetation, steaming volcanic vents, and natural hot springs, the bay was much deeper than it is today. A series of earthquakes and tremors have since raised the sea bed so that today it lies just 3-4 meters below the surface. We arrived at first light on a Monday, after a 4.5 day passage from Fiji.Immediately, we realized we were in a new kind of South Pacific. Earlier, I have written about the gradual leaving-behind of western-influenced cultures and norms, and the island of Tanna in the country of Vanuatu, completes the departure. Around us are puffs of steam emanating from jungle canopies, bamboo-and-bark ladders descending to the hot springs welling up along the steep shoreline, and the happy whoops of women and children coming from several distinct collections of thatched huts atop the vegetation-lined cliffs that line this bay. Some of the huts are built in trees, and that night, as we survey the land, it is apparent that there is no electricity whatsoever in these villages. It's dark like the ocean at midnight.

The next day, we go ashore and pay our respects to Stanley, the chief of Ireupuow. He is the second son of Chief Ronnie, the former chief, who died just over a year ago. Unusually for the South Pacific, in Vanuatu, the traditional patrimonial lineage passes over the first-born and it is the second son who inherits the title. When asked, Stanley later relates the Biblical story in Genesis where Isaac's second son, Jacob, at the urging of his mother Rebecca, deceives his father and gains the birthright and blessing that ought to have been the province of Esau, the oldest. In Vanuatu, at least in this village, the scripture is used to explain the cultural tradition of the second son chosen for lineal authority. There's a Presbyterian church (more a thatch-covered, wall-less canopy, with rough-hewn benches), a cinder block Seventh Day Adventist building, and, marked by a red cross, the village's dominant sect: the Jon Frum Movement.

The next day, we go ashore and pay our respects to Stanley, the chief of Ireupuow. He is the second son of Chief Ronnie, the former chief, who died just over a year ago. Unusually for the South Pacific, in Vanuatu, the traditional patrimonial lineage passes over the first-born and it is the second son who inherits the title. When asked, Stanley later relates the Biblical story in Genesis where Isaac's second son, Jacob, at the urging of his mother Rebecca, deceives his father and gains the birthright and blessing that ought to have been the province of Esau, the oldest. In Vanuatu, at least in this village, the scripture is used to explain the cultural tradition of the second son chosen for lineal authority. There's a Presbyterian church (more a thatch-covered, wall-less canopy, with rough-hewn benches), a cinder block Seventh Day Adventist building, and, marked by a red cross, the village's dominant sect: the Jon Frum Movement. In the 1930s, frustrated by the rigidity of the Presbyterian missionaries, Tanna natives began to talk about a (still) mysterious person named Jon Frum - said to be the brother of the god of Mt. Tukosmera, one of the island's several volcanos. By the time WW II came to the islands, the appearance of ships, jeeps, freezers, etc. seemed to bear out one of Jon Frum's central prophecies: the impending arrival of an abundance of wealth. Naturally, the Red Cross, with its clinics and hospitals accompanied the troops. Soon, Tanna followers of Jon Frum began to display red crosses, which today are visible in most of the villages. Chief Stanley did allow as to how many of his villagers attended all three churches, and smiled when I pointed out that it's important to cover all one's bases. When asked how long villagers would wait from the (re?)arrival of Jon Frum, one reference cites a reasonable response: "How long have Christians waited?"

In the 1930s, frustrated by the rigidity of the Presbyterian missionaries, Tanna natives began to talk about a (still) mysterious person named Jon Frum - said to be the brother of the god of Mt. Tukosmera, one of the island's several volcanos. By the time WW II came to the islands, the appearance of ships, jeeps, freezers, etc. seemed to bear out one of Jon Frum's central prophecies: the impending arrival of an abundance of wealth. Naturally, the Red Cross, with its clinics and hospitals accompanied the troops. Soon, Tanna followers of Jon Frum began to display red crosses, which today are visible in most of the villages. Chief Stanley did allow as to how many of his villagers attended all three churches, and smiled when I pointed out that it's important to cover all one's bases. When asked how long villagers would wait from the (re?)arrival of Jon Frum, one reference cites a reasonable response: "How long have Christians waited?" As we got to know Stanley, he let us know that there are actually two chiefs in each village - one ministers to the day-to-day issues and grievances; the other sets the longer-term direction and policies of the village. Stanley inherited the latter role; his father wore big shoes: he built a so-called "yacht club," creating a formal port of entry for Port Resolution (allowing boats to arrive at this upwind anchorage before proceeding downwind to the rest of the archipelago); he revitalized a decaying set of school buildings and has created a primary and secondary school for surrounding villages; and he had built (and then, after going off to school, personally staffed) a health clinic for the villages.

As we got to know Stanley, he let us know that there are actually two chiefs in each village - one ministers to the day-to-day issues and grievances; the other sets the longer-term direction and policies of the village. Stanley inherited the latter role; his father wore big shoes: he built a so-called "yacht club," creating a formal port of entry for Port Resolution (allowing boats to arrive at this upwind anchorage before proceeding downwind to the rest of the archipelago); he revitalized a decaying set of school buildings and has created a primary and secondary school for surrounding villages; and he had built (and then, after going off to school, personally staffed) a health clinic for the villages. To appreciate the value of these three innovations, it's helpful to know that there are no paved roads on the island, and that I can count the number of cars within 25 miles on one hand. There is no indoor plumbing, and all food is cooked over wood fires in a hut designated for cooking. A village itself is traditionally laid out: about 20 families each occupy about an acre of land, with each plot surrounding a large common area consisting of a decidedly-unlevel soccer field. The huts are each about 15 feet wide by about 30 feet long, whose structures rely on hand-hewn branches from the banyan tree. The outside coverings vary: some use the unstripped reeds known as jungle cane, laid one against the other, vertically, slipped between horizontal runs of small branches. Bindings are twisted coconut fiber, tied in knots at the junctures. Others also use the cane, but stripped to its inner core, and then they use two layers - an inside wall and an outside wall, with dried palm leaves laid as a sort of insulation between the two vertical sets of cane. Still others use scraps of galvanized metal, haphazardly arranged and wedged, and still others use palm leaves, thatched. The most elaborate are the woven walls, where strips of palm leaves are interwoven into elaborate cross-hatch patterns. All of the roofs use the palm leaves, woven into thatches that lay, shingle-like, across the banyan branch roof structure. Windows are openings in the walls, with "planks" of palm trunks arranged into a covering of sorts.

To appreciate the value of these three innovations, it's helpful to know that there are no paved roads on the island, and that I can count the number of cars within 25 miles on one hand. There is no indoor plumbing, and all food is cooked over wood fires in a hut designated for cooking. A village itself is traditionally laid out: about 20 families each occupy about an acre of land, with each plot surrounding a large common area consisting of a decidedly-unlevel soccer field. The huts are each about 15 feet wide by about 30 feet long, whose structures rely on hand-hewn branches from the banyan tree. The outside coverings vary: some use the unstripped reeds known as jungle cane, laid one against the other, vertically, slipped between horizontal runs of small branches. Bindings are twisted coconut fiber, tied in knots at the junctures. Others also use the cane, but stripped to its inner core, and then they use two layers - an inside wall and an outside wall, with dried palm leaves laid as a sort of insulation between the two vertical sets of cane. Still others use scraps of galvanized metal, haphazardly arranged and wedged, and still others use palm leaves, thatched. The most elaborate are the woven walls, where strips of palm leaves are interwoven into elaborate cross-hatch patterns. All of the roofs use the palm leaves, woven into thatches that lay, shingle-like, across the banyan branch roof structure. Windows are openings in the walls, with "planks" of palm trunks arranged into a covering of sorts.The water for the village comes as a result of the vision and hard work of Chief Ronnie's father, who mobilized the village decades ago to dig a trench from a mountain spring 10 miles away, and to lay a water pipe. The village has a handful of gravity-fed pumps scattered about for washing and cleaning, and many villages lack even a supply of water, requiring women to walk to nearby springs lugging jugs and bowls.

Each family's "compound" has a slightly different look and feel, but in general, imagine a collection of thatched huts opening on a common courtyard of sorts, with the entire collection of family compounds surrounding the soccer field. The village straddles the bay, where we are anchored, and, just across the promontory, lies the southern ocean-abutting edge of Tanna, with its picture postcard white beaches, the gentle surf of the South Pacific on the shore side of a small offshore reef. Children run and play, men lounge, and the women work. Pigs and chickens grub for food among the grasses. Women work hard, from dawn to late evening, collecting firewood, food, cleaning, raising children, weaving, and tending to gardens.

Each family's "compound" has a slightly different look and feel, but in general, imagine a collection of thatched huts opening on a common courtyard of sorts, with the entire collection of family compounds surrounding the soccer field. The village straddles the bay, where we are anchored, and, just across the promontory, lies the southern ocean-abutting edge of Tanna, with its picture postcard white beaches, the gentle surf of the South Pacific on the shore side of a small offshore reef. Children run and play, men lounge, and the women work. Pigs and chickens grub for food among the grasses. Women work hard, from dawn to late evening, collecting firewood, food, cleaning, raising children, weaving, and tending to gardens. The next day, we took a teeth-rattling, bone-jarring 4-hour, 25 mile trip in the village's pickup truck (along with about 15 villagers) to complete our immigration and custom formalities. On the way, we had to wait an hour for the rain-swollen, ash-bottomed river that runs alongside Mt. Yasur, (the very active volcano that attracts boaters and tourists alike) to subside sufficiently to allow the truck to cross. Eventually, after much hemming and hawing by the villagers, the driver put the truck into gear, headed down the ashen slope, turned the wheels upstream, and, with Jennifer and I mentally planning water escapes, crossed the 2 foot deep, 75 foot wide river safely.

The next day, we took a teeth-rattling, bone-jarring 4-hour, 25 mile trip in the village's pickup truck (along with about 15 villagers) to complete our immigration and custom formalities. On the way, we had to wait an hour for the rain-swollen, ash-bottomed river that runs alongside Mt. Yasur, (the very active volcano that attracts boaters and tourists alike) to subside sufficiently to allow the truck to cross. Eventually, after much hemming and hawing by the villagers, the driver put the truck into gear, headed down the ashen slope, turned the wheels upstream, and, with Jennifer and I mentally planning water escapes, crossed the 2 foot deep, 75 foot wide river safely.Once in Lenakel, a dusty town of small cinder block shops and buildings, I sat and talked with the head of the local fisheries development program, charged with encouraging locals to expand their fishing activities. One thing led to another, and as we waited until 2 pm for the promised 1 pm opening of the immigration office, we got to talking about the roles of men and women in Vanuatu society. Like Stanley, in his description of the Genesis treatment of Isaac, Esau, and Jacob , the Bible immediately came into play: he too cited a verse from Genesis: "Woman's desire shall be to thy husband, and he shall rule over thee." To this member of the Vanuatu middle class, women exist solely to serve man, and women had no say whatsoever in decisions, and were required to do most, if not all, of the work. Historically, men would pull the front teeth of their wives to signify ownership, and more recently, the government has capped the amount a man must pay the family of his wife-to-be for the privilege of marriage.

I mentioned that I had seen a woman managing the local bank (we had to change money), and he allowed as to how in the workplace, women could occupy management, but once back in the village and the home, the man was in charge. Sitting beside him a strikingly- beautiful, well-dressed woman nodded her head in supportive agreement. By then, our conversation had become friendly enough that I felt comfortable smiling and tossing a small pebble at his feet, as he sat across the way on a similar bench. "Pretty good deal for the men, no?" He smiled, and said it's always been that way and would always be that way.

Later, as we bumped and rolled our way back to the village, we spied dozens of women walking along the rutted road, carrying loads of firewood, baskets of yams, and swatting flies and mosquitoes. One step and then another, after a day collecting fuel for the evening's cook fire, food for the family. Nothing romantic here; mud-splattered clothes, tired eyes, and a pervasive sense of just another day in a subsistence world.

The next day, as we toured the village with Stanley, and on our way to the white sand beach, we passed through a compound of unwalled, roofed shelters, each with rough-hewn benches under the cover. This was the man's compound, where each day, in the late afternoon, the men of the village would gather and drink kava, the slightly narcotic drink that is made from the roots of a local pepper plant. No women are allowed; Stanley explained that this is where the men gathered daily to talk, discuss, and resolve any issues or problems arising in the village. Back in the village, the women would be cleaning the dishes, washing the clothes, and putting the children to bed.

The village we were fortunate enough to visit had several graves surrounded by rusted wrought iron fence stakes; one commemorated a missionary who had died in 1893, well after Captain Cook arrived. After several unsuccessful attempts to land (many were murdered by the natives), the missionaries finally established footholds in many of the islands that were then called the New Hebrides (Vanuatu became independent in 1980). However, these missionaries were unable to stem one of the more reprehensible practices of Europeans - the so-called "blackbirding," where unscrupulous merchants kidnapped natives by the thousands to provide cheap (slave) labor in the booming sugar, banana and coconut plantations in Fiji, Tonga, and elsewhere. To combat this, both the French and English governments sought to police the islands of Vanuatu, and, eventually and unworkably, formed a "condominium" government, with each foreign power establishing its own government, schools, courts, etc. To this day, many ni-Vanuatu speak at least four languages: the local village tongue (several hundred dialects); Bislama - a curious pidgin English; proper English, and French. Tragically, until independence, each European government tended to look only after its own citizens. Only the missionaries saw fit to focus on the locals. Thus, a deeply religious people, and a curiously strong mix of Biblical literalism coupled with pre-European cultural traditions.

The village we were fortunate enough to visit had several graves surrounded by rusted wrought iron fence stakes; one commemorated a missionary who had died in 1893, well after Captain Cook arrived. After several unsuccessful attempts to land (many were murdered by the natives), the missionaries finally established footholds in many of the islands that were then called the New Hebrides (Vanuatu became independent in 1980). However, these missionaries were unable to stem one of the more reprehensible practices of Europeans - the so-called "blackbirding," where unscrupulous merchants kidnapped natives by the thousands to provide cheap (slave) labor in the booming sugar, banana and coconut plantations in Fiji, Tonga, and elsewhere. To combat this, both the French and English governments sought to police the islands of Vanuatu, and, eventually and unworkably, formed a "condominium" government, with each foreign power establishing its own government, schools, courts, etc. To this day, many ni-Vanuatu speak at least four languages: the local village tongue (several hundred dialects); Bislama - a curious pidgin English; proper English, and French. Tragically, until independence, each European government tended to look only after its own citizens. Only the missionaries saw fit to focus on the locals. Thus, a deeply religious people, and a curiously strong mix of Biblical literalism coupled with pre-European cultural traditions. Stanley is building a new house, one with a small 7x7 foot "room" for his daughter, Naomi. He does not have a first son, and seems not to have any immediate plans for more children. We never met his wife, although we did meet his sisters and brother. As we left, he was walking over to the kava huts. Smoke seeped out from the huts dedicated to cooking, and women were walking back from the jungle, with large bundles of sticks on their shoulders. The kids were gathering for the afternoon soccer game, having just joined the school's elders in a traditional dance celebrating the completion of exams and thanking the teachers for their service. Around the perimeter of the bay, steam wafted from volcanic vents, and the volcano's ash cloud covered the western sky. We settled down for a dinner of Indonesian rice and chicken, and the nightly rains began to fall.

Stanley is building a new house, one with a small 7x7 foot "room" for his daughter, Naomi. He does not have a first son, and seems not to have any immediate plans for more children. We never met his wife, although we did meet his sisters and brother. As we left, he was walking over to the kava huts. Smoke seeped out from the huts dedicated to cooking, and women were walking back from the jungle, with large bundles of sticks on their shoulders. The kids were gathering for the afternoon soccer game, having just joined the school's elders in a traditional dance celebrating the completion of exams and thanking the teachers for their service. Around the perimeter of the bay, steam wafted from volcanic vents, and the volcano's ash cloud covered the western sky. We settled down for a dinner of Indonesian rice and chicken, and the nightly rains began to fall.

And the women - the girls we saw in the village school; the daughter of the well-dressed woman in Lenakel; Naomi - what will become of the women of Vanuatu?